Delivering on Climate Justice

Fostering inclusive adaptation and resilience building in the face of mounting losses

By FP Analytics, with support from The Open Society Foundations

Lives and livelihoods are at stake as climate change poses significant and compounding threats to global security, safety, and equity. Left unchecked, the losses and damages that countries will incur because of climate change are far-reaching, including impacts related to health, food, water, economic growth, and fragility. These and other impacts, however, will not be evenly distributed. Around the world, rising temperatures are disproportionally upending the lives of marginalized groups and vulnerable communities, including women and girls, persons with disabilities, displaced persons, and ethnic and racial groups. For the world’s least-developed countries (LDCs) and small island developing states (SIDS), climate change is an existential threat as extreme weather events such as floods, hurricanes, and droughts, increase in frequency and intensity. Yet, collective efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) and provide financial support to those most at risk are currently insufficient to tackle the speed and scale of climate impacts. Effective climate change adaptation globally is a matter not only of environmental justice but also of social and economic justice, warranting a people- and planet-centered approach.

To coincide with the UN Conference of Parties (COP) 27 at Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, in November 2022, FP Analytics produced this issue brief with support from the Open Society Foundations to analyze the cascading impacts of climate change on human security and to examine the roles of multi-stakeholder partnerships and innovative climate finance solutions to support climate justice, resilience building, and inclusive adaptation.

Threatening Lives, Upending Livelihoods: The Mounting Impacts of Climate Change

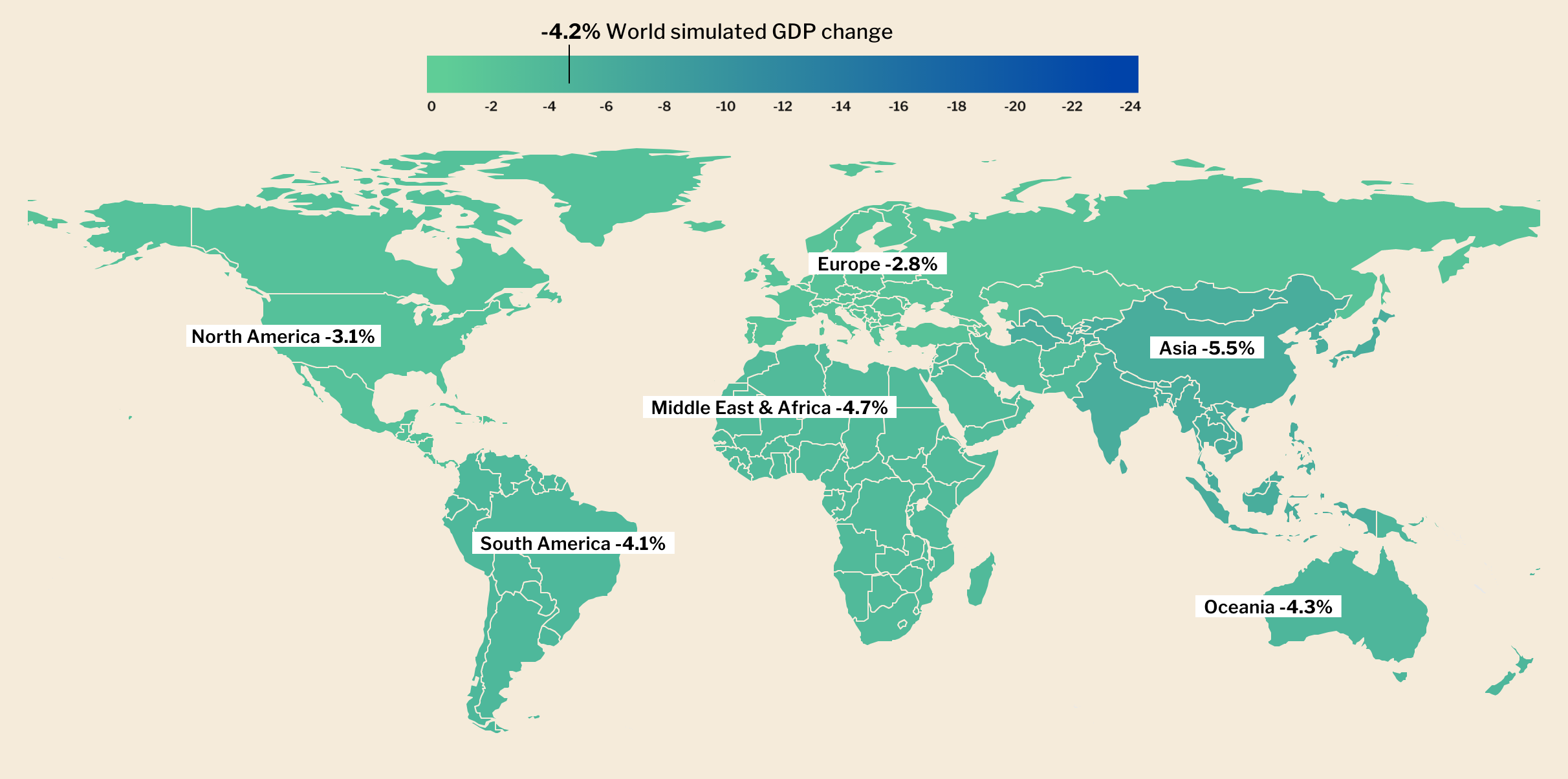

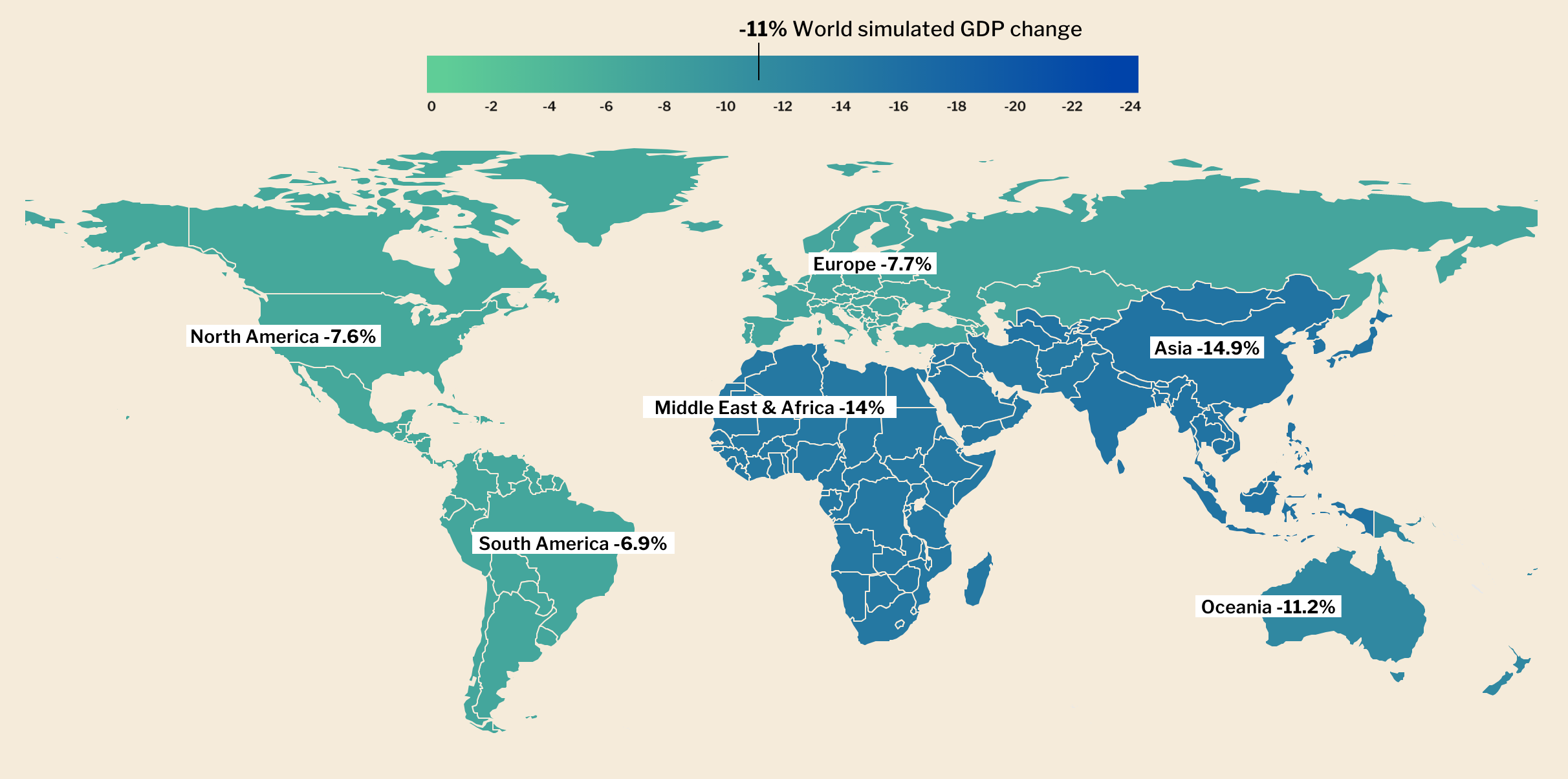

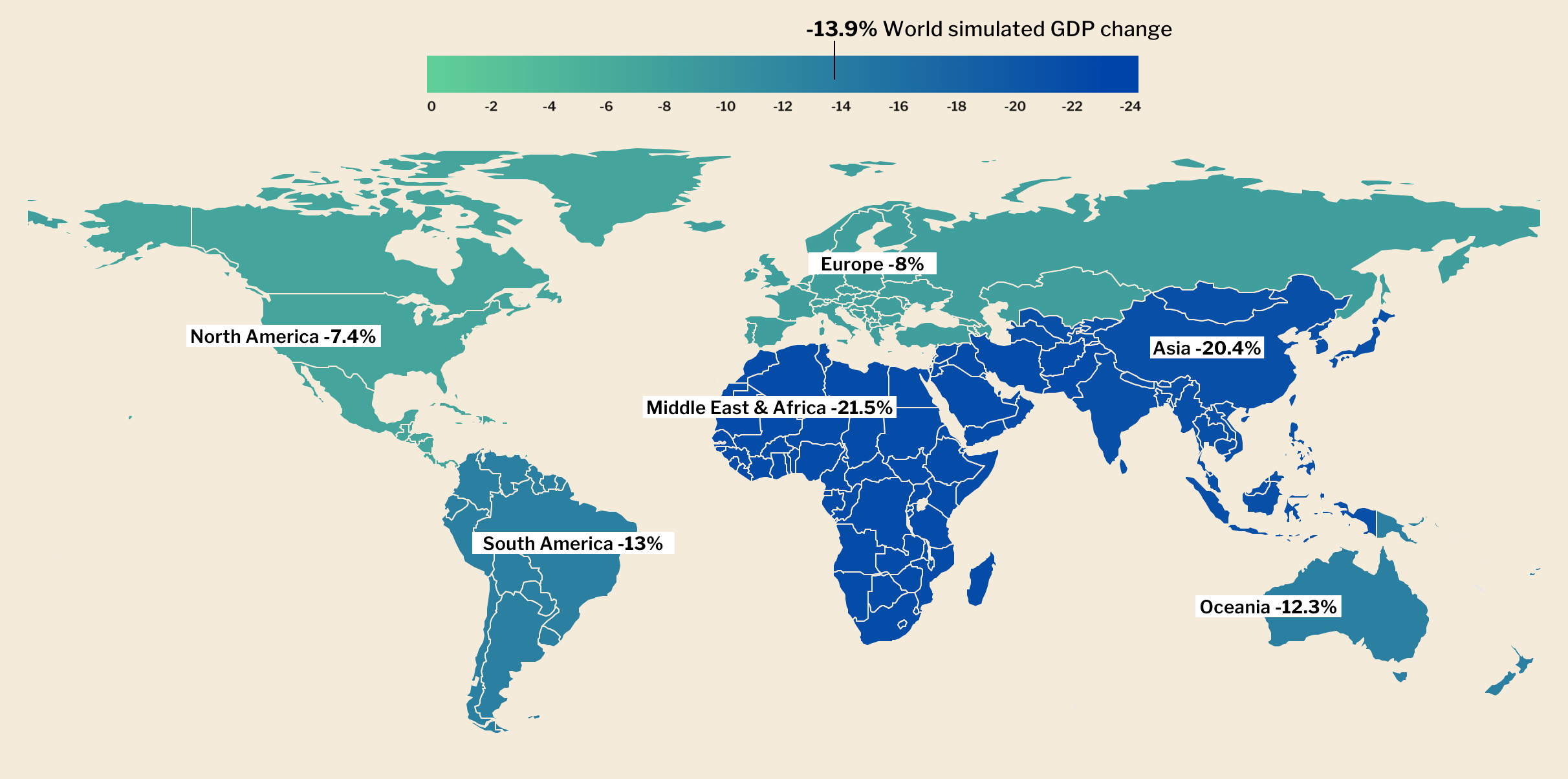

Climate-related losses and damages caused by sudden-onset extreme weather events or slow-onset environmental degradation can significantly disrupt critical sectors of the global economy and threaten public health, food security, and political stability, especially of the world’s most vulnerable communities. Failure to coordinate on global climate action could result in widespread economic downturn. Estimates suggest that by 2050, global GDP could shrink by 18 percent in worst-case climate scenarios. The impacts on economic growth will be the most severe for LDCs and SIDS, with future costs of losses and damages for developing economies estimated to reach up to $1.7 trillion annually by 2050.

Simulated Regional GDP Losses By 2050

Select one of the three warming scenarios to see the regional projected GDP impact

Data source: Swiss Re

Mitigating losses and damages through resilience building and lowering carbon emissions is vital to achieving positive economic growth and protecting development gains, such as poverty reduction and gender equality advances, made over the last several decades. For the most climate-vulnerable communities—especially in low-lying, disaster-prone areas—resilience-building includes, but is not limited to, fortifying public health, food, and political systems to safeguard livelihoods and strengthen people’s basic rights to security, safety, and a healthy environment in the face of worsening crises.

Health Impacts of Climate Change

Climate change endangers global public health through many channels, from extreme heat-induced illnesses and air pollution causing respiratory and cardiovascular distress to negative mental and physical health from catastrophic events and loss of ancestral land or cultural traditions, as well as contaminated water supplies. In low-income communities across all countries, this threat is compounded by lack of stable access to quality health services, housing, food, and water. For example, the morbidity and mortality impacts of extreme heat-related illnesses are concentrated within low-income groups, the elderly, and women. Climate change will not only increase the global incidence of disease, but also heighten and concentrate economic vulnerability to health stress in uninsured and financially insecure populations. In Pakistan, medical workers are working to forestall a worsening public health crisis after catastrophic flooding in 2022 left 33 million people living in makeshift homes surrounded by disease-ridden standing water, and 2,000 health facilities were rendered fully or partially inoperable, restricting access to medical care. Pakistan, regarded the eighth most vulnerable nation to climate risk, has faced 173 extreme weather events in the last two decades, and the impact on low-income communities in regions like Sindh and Baluchistan is exacerbated by poor governance and a lack of investment in the infrastructure needed to build resilience.

Climate Change and Intensifying Global Food Insecurity

Rising global temperatures are contributing to freshwater shortages, land degradation, flooding, and drought; altered crop yield; reduced labor productivity; and compromised global supply chains. In 2020, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projected a 7.6 percent median increase in cereal prices by 2050 due to climate change, even before the onset of severe food price inflation exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. New data from 103 countries shows that increased incidence and intensity of extreme heat due to climate change accounted for an estimated additional 98 million people reporting moderate to severe food insecurity in 2020 compared to the annual average from 1981-2010. Climate change threatens both the quantity and quality of crops, precipitating massive economic losses for agriculture-dependent economies and widespread undernutrition in low- and middle-income communities. In Eastern and Southern Africa, where a historic drought has aggravated ongoing food insecurity, the World Bank has invested $2.3 billion in a Food Systems Resilience Program to strengthen crisis response and develop long-term solutions. However, climate-induced shocks to the food system are happening every 2.5 years on average, and adaptation to the resounding impacts of these events will require scaling up international investment and public-private partnerships.

A survey by the Open Society Foundations conducted in mid-2022 found that anxiety about rising food prices is extensive, with 80 percent of respondents surveyed in Latin America, 77 percent of respondents in sub-Saharan Africa, and 33 percent of respondents in Western Europe worrying that their family will go hungry.

Climate-related Disruptions Could Exacerbate Civil Unrest and Conflict

In countries facing governance challenges, vast inequality, and lethargic development, humanitarian aid is often the main source of relief for marginalized communities, though it is typically insufficient to support climate adaptation. The World Bank estimates that up to 132 million people are at risk of falling into extreme poverty due to climate change, with the worst impacts concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Those who are already in precarious positions due to poverty or conflict have fewer resources to cope with natural disasters and slow-onset environmental degradation, which further limits their livelihood options and resilience to climate change. Women and girls are particularly at risk, as they face structural inequalities such as lack of property rights and inadequate access to paid work or education that restrict their ability to make decisions about how to cope with the effects of climate change. Climate-related stresses on the environment and livelihoods of populations are increasingly contributing to migration, which is not always voluntary and typically exacerbates gender inequalities. An estimated 80 percent of climate-displaced persons are women, who tend to face higher risks of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), abuse, and exploitation while in transit and in destination countries. Climate-related migration can also fuel existing tensions between populations and increase the risk of violent conflict, as observed in Iraq and South Sudan. Moreover, the knock-on effects of climate-related conflict and unrest engender widespread economic challenges for noncontiguous regions through the disruption of international trade, manufacturing, and supply chains, further augmenting risks to the global economy and widening inequalities between developed and developing countries.

Climate Change Risks Worsening the Global Energy Crisis

Global warming and climate-related extreme weather events are putting pressure on critical energy infrastructure, undermining energy security, and causing widespread power outages globally. Currently, 47 percent of the world’s thermal power plant capacity is located in high water-stressed areas, and about 25 percent of global electricity networks face high risks of destructive cyclone winds. Reducing dependence on fossil fuels and facilitating a just clean energy transition are key, including expanding energy access and overcoming energy poverty among the poorest and most marginalized communities. Estimates show that investing in renewable energy technology could end energy poverty, reduce emissions by four billion tons, and create more than 25 million jobs in the power sector in Africa and Asia by 2030.

In LDCs and SIDS, access to energy is a fundamental need that underpins their abilities to withstand warming temperatures and develop across critical sectors. Fifty-two percent of people in LDCs—about 570 million people or two-thirds of the world’s population—do not have electricity access, especially in rural areas. While promising efforts are emerging to strengthen communities’ energy security, they need investment to scale up. For example, Weatherizers Without Borders is an Argentina-based non-profit that aims to improve energy efficiency and end energy poverty in Latin America. Another example is Grameen Shakti, which supplies renewable energy technologies to rural households in Bangladesh, one of the most climate-vulnerable countries. These types of local and regional efforts highlight how cross-sectoral and cross-country partnerships can support local efforts to propel countries toward carbon-neutral pathways with long-term economic and environmental impacts.

Redress and Compensation for Climate-induced Loss and Damage

The burden of loss and damage accumulates over time and increases systemic vulnerability, especially when accounting for non-economic and often irreparable losses that involve the destruction and displacement of lives, cultures, traditions, lands, and the resulting psychological and physical trauma. The compounding effects of loss and damage results in reduced adaptive capacity for the next climate disaster, contributing to a widening wealth gap between developing and developed economies. The Climate Vulnerable Forum, which consists of 55 of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries, has been calling for a commitment to compensation from wealthy countries that have historical and ongoing responsibility for the majority of GHG emissions, including a “dedicated financing facility as a part of funding arrangements for addressing loss and damage.”

The response to this proposal for a compensation mechanism has been mixed amongst advanced economies, with skeptics concerned about taking on financial and legal liability for loss and damage. Some wealthy countries have offered support by way of data collection and technical assistance, such as funding the UNFCCC’s new Climate Technology Centre & Network (CTCN) for capacity building. The G77 and the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) have criticized these technical efforts as inadequate, noting that the technology and data resources offered by developed economies have little impact without financial investments to develop and implement resilience measures. Proponents of compensation also emphasize that regardless of a legal obligation to compensate, a moral imperative exists, noting the disproportionate impacts of climate change on those who have contributed least to its worsening.

The Warsaw Mechanism established at COP 19 in 2013 recognizes the disproportionate impact of climate change on vulnerable populations and emphasizes the need for global cooperation and financing to build the adaptive capacity of the most-affected communities. However, it has been criticized for failing to facilitate financial support from wealthy countries to LDCs and SIDS. At COP 26 in 2021, the G77—a coalition of 134 developing economies—pushed to create a financial facility to compensate victims of loss and damage. A financial facility is a stand-alone mechanism with multiple contributors and beneficiaries, as distinguished from a financial fund, which is a one-way exchange between donor and recipient. However, both the U.S. and the EU argued that they would not support the measure and instead supported strengthening technical assistance programs. At COP 21 in Paris, Article 8 of the 2015 Agreement reinforced support for the Warsaw Mechanism and put loss and damage as an approach on equal footing with mitigation and adaptation. However, the agreement specified that it does not “involve or provide basis for any liability or compensation.” Without any means to compel universal participation in financing for loss and damage, some governments have taken unilateral action to advance the discussion. Scotland was the first advanced economy to act on this effort, contributing $1.4 million in 2021 to the Climate Justice Resilience Fund (CJRF) to compensate climate-vulnerable communities. The Wallonia region of Belgium pledged €1million, and Denmark followed suit in 2022, pledging $13 million. However, these pledges fall far short of the vast support that LDCs and SIDS require for effective and inclusive adaptation. The UNFCCC Secretariat, at the G77’s insistence, has confirmed the inclusion of a subitem on a loss and damage financing facility in the provisional agenda of COP27, creating further pressure on the participants to revisit the conversation. As the urgency of building climate resilience for the most vulnerable countries grows, so too has the focus on opportunities for operationalizing financing for loss and damage that help empower affected communities.

Leveraging Innovative Financial Solutions to Foster Inclusive Climate Adaptation

Expanding access to development aid and finance that blends public, private, and donor investments is integral to building critical infrastructure, developing competitive markets, and facilitating a just net-zero transition. Over the last decade, total climate finance has steadily increased—reaching $632 billion in 2020—but funding needs to increase by at least 590 percent, or $4.35 trillion annually, by 2030 to meet global climate goals. For communities whose climate finance needs exceed what their domestic resources can provide, international and private funding is essential for them to meet their nationally determined contributions. For example, the Pacific Islands face a significant finance gap with some nations’ climate adaptation budgets totaling over 200 percent of their GDP. Yet in 2020, mitigation finance accounted for over 90 percent of total climate finance, whereas adaptation finance accounted for only 7 percent, and the remaining covered both. In short, financing to facilitate climate adaptation significantly lags.

Developing economies depend on foreign investments and international aid to support their efforts to address climate change, but weak legal and regulatory environments, underdeveloped lending, limited technical expertise, foreign exchange and political instability risks can deter public and private investments. Since COP 15 in 2009, wealthy countries have recognized the need to increase finance access to low- and lower-middle income countries, but developed economies are falling short of delivering on their annual $100 billion climate financing pledge. In 2019, of the total $79.6 billion worth of climate finance provided by developed countries, LDCs, and SIDS received only 19 percent ($15.4 billion) and two percent ($1.5 billion), respectively. SIDS, in particular, are the most economically vulnerable of all developing countries, according to the UN Economic Vulnerability Index. But less than 2 percent, or $500 million, of climate adaptation finance for SIDS came from private sources, with most private adaptation investments going to higher-income countries, namely Canada and the United Arab Emirates. In low- and lower-middle income countries, where small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for some 35 percent of GDP, increasing access to climate adaptation financing for SMEs has also proven challenging due to structural barriers to financial markets and international investments, such as complex accreditation processes and insurmountable up-front costs.

To date, the majority of the climate-related funding has been in the form of debt. Already highly indebted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, debt burdens are rising as developing economies continue to borrow money to address the risks and losses stemming from climate change, economic downturn, and other compounding challenges such as fragility. In 2021, the global issuance of sustainable debt grew to record levels reaching $1.4 trillion, and projections estimate that it could reach $3.8 trillion by 2025. Although international financial institutions (IFIs) and development banks provide low-cost concessional loans, about half of the total loans for climate finance are not below market rate. Recognizing the need to increase access to debt-free or low-interest financing, in August 2021, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Board of Governors approved the issuance of $650 billion worth of special drawing rights or other low-interest, long-term debt instruments to help finance developing countries’ climate adaptation plans, but the majority of SDR issuance has been made to advanced economies.

However, as climate impacts become more severe, and debt burdens, particularly for low and low-middle income countries rise, some leaders such as Barbados’s Prime Minister Mia Mottley have called for the creation of new and alternative financial instruments. One proposal is a loss and damage fund where one percent of revenues from the sale of fossil fuels from wealthy, high-emitting countries—equivalent to $70 billion—would be collected annually and used to support those communities that have suffered from climate-related disasters. Such a mechanism could be included in existing climate financing structures, such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF), which aims to help developing countries respond to climate change and is mandated to provide loss and damage support. As of 2021, over 24 percent of its projects addressed loss and damage, and 16 percent of projects directly linked loss and damage as part of their main activities. Other multilateral financing sources, such as the World Bank’s Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) and multi-donor trust fund, the Global Risk Financing Facility (GRiF), also provide funding and financial tools to address loss and damage.

With rising global temperatures exacerbating global economic inequality, the worst-affected developing economies are demanding that, in addition to meeting annual climate finance pledges, wealthy countries allocate resources to address loss and damage from climate change. This includes providing support to communities in the aftermath of the loss of an asset, such as cropland that has been rendered unproductive following an extreme weather event, which is often not covered by adaptation finance. According to the Vulnerable Twenty (V20) Group of Ministries of Finance—a coalition of economies that are systemically vulnerable to climate change—the most at-risk countries among them have lost more than half of all economic growth since 2000 due to climate change. The V20 has called for reforms to the global financing architecture, including support to reduce debt burdens and increase grant-based funding for climate adaptation. The existential threat posed by climate change, combined with mounting economic costs and a lack of follow-through by wealthy countries on climate funding pledges, prompted Tuvalu, Palau, and Antigua and Barbuda, to establish the Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law (COSIS). Parties to the Commission hope to leverage international law to seek damages and hold major carbon-emitting countries accountable for their role in worsening climate change.

Still, effective action goes beyond increasing access to finance. While funding is necessary to rebuild and fortify infrastructure as well as to support resilient livelihoods, other strategies and tools are also needed to support adaptive capacity. For example, indigenous people and local communities (IPLCs) often have a synergistic, intergenerational relationship with the lands they inhabit, which fosters greater protection of forest ecosystems’ biodiversity and natural resources. Indigenous and local knowledge, and protections for IPLC’s ancestral lands, resources, and territories need to be better integrated into the international community’s efforts to address climate change. IPLCs representation and leadership in adaptation efforts can be elevated through political will backed by conducive policies and sustained investments. Similarly, innovative climate finance tools and adaptation strategies that strengthen energy security and support net-zero transitions in developing economies need to be elevated and scaled up through greater public-private partnership and expanded investment.

Fostering Climate Justice and Building Resilient Systems Are Urgent

Vulnerable countries are innovating climate finance responses.

Fiji Leads the Way in Creative Financing for Climate Resilience

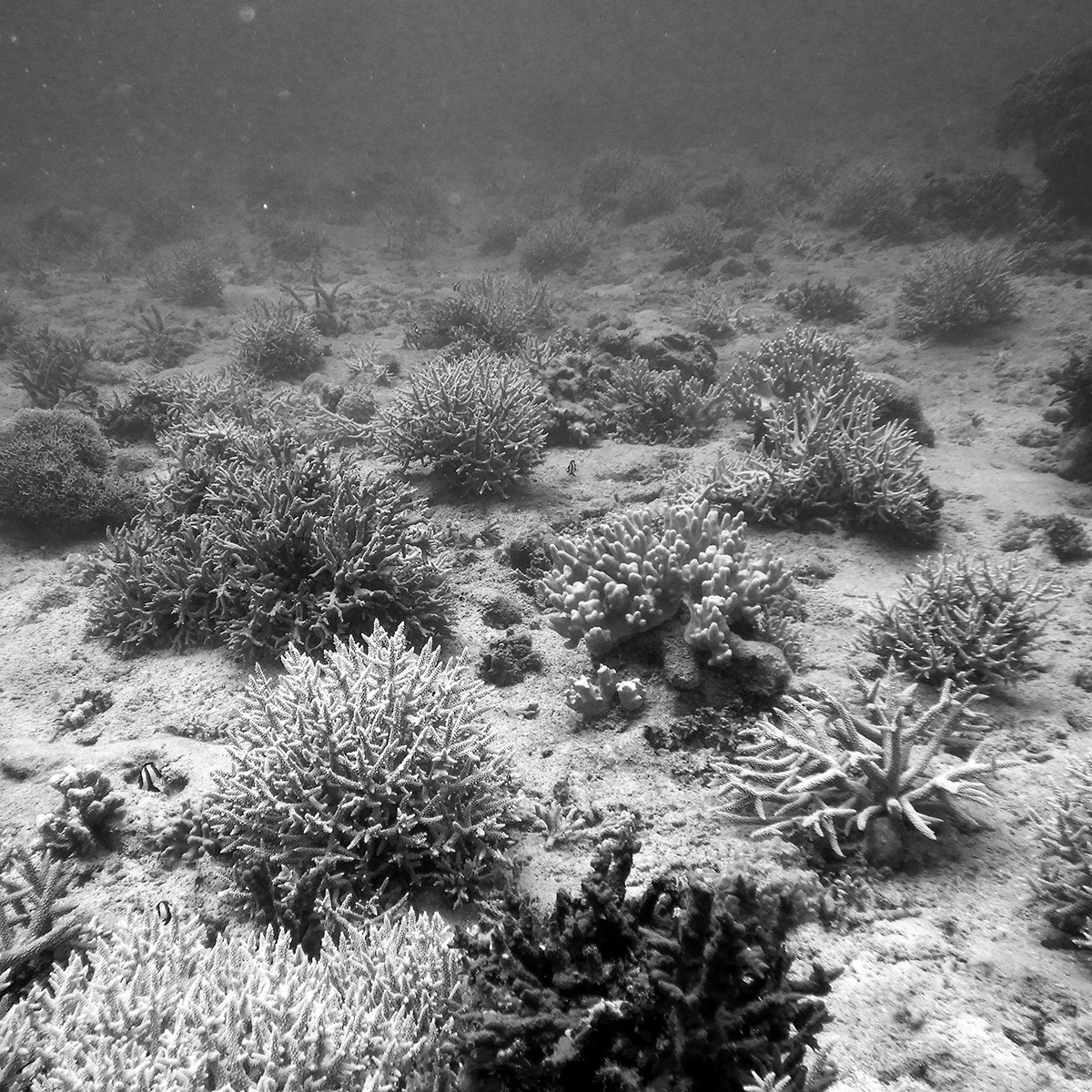

In 2018, Fiji became the first developing economy to release a sovereign green bond, following its presidency of the COP 23 convening. The initial tranche raised $50 million and was launched with the support of the IFC, World Bank, and government of Australia. Green bonds present an opportunity for governments to mobilize development finance and private-sector investment while maintaining control over how the money is spent. Research by the World Bank and the government of Fiji suggests that the island nation is likely to require at least $4 billion of investment by 2030 to meet myriad challenges brought on by climate change. Across the region, at least 50,000 Pacific Island residents are at risk of being displaced by natural disasters such as tropical cyclones and flooding, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center. The initial investment raised has been used for a series of climate adaptation plans, including meeting government goals of shifting to 100 percent renewable energy sources, reducing carbon emissions by 30 percent by 2030, and investing in crop resilience, flood management, and building and adapting weather-resilient schools. In 2021, Fiji followed up its successful green bonds launch with a new tranche of blue bonds (focused on protecting oceans and marine biodiversity), supported by the British government and the UN Development Programme (UNDP), to deliver a sustainable blue economy, create jobs, and protect marine biodiversity.

PHOTO: VICTOR BONITO/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Belize Restructures Debt in Pursuit of Ocean Conservation

In 2021, Belize announced that it would take part in the world’s largest debt-restructuring agreement to-date for the purposes of marine conservation, in partnership with U.S.-based non-profit The Nature Conservancy. As part of the organization’s ongoing blue bonds program, the government of Belize has received a $553 million loan from Credit Suisse—with risk insurance provided by the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC)—to repurchase commercial debt, reduce its debt burden, and generate around $4 million per year to invest in ocean conservation projects. As part of the agreement, Belize has committed to protect 20 percent of its ocean—including coral reefs, mangroves, and fish spawning sites—strengthen frameworks for domestic and high seas fisheries, and establish a new regulatory framework for coastal blue carbon projects. This approach has worked well in the past; a 2016 debt-restructuring agreement with the Seychelles has enabled its government to generate approximately $430,000 per year and to protect 410,000 square kilometers of ocean.

PHOTO: PEDRO PARDO/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Rwandan Green Investment Generates Jobs, Energy, and Trees

Launched in 2012, the Rwanda Green Fund (FONERWA) is the largest of its kind in Africa, and one of the first national investment funds focused on environmental conservation and climate change mitigation in the region. The fund invests in public and private projects driving transformative change within Rwanda, with private companies required to match funding by at least 25 percent. Still heavily reliant on agriculture—the sector generates an average of one-third of GDP—Rwanda is already significantly impacted by climate change, particularly changes in rain patterns, and is expected to experience an additional 2.5°C in warming by 2050, which will threaten the environment, lifestyle, and employment of its citizens. Since its launch, FONERWA has produced a substantial impact: nearly $40 million has been invested in more than 35 projects, generating more than 137,000 jobs, and connecting over 57,000 households with clean off-grid energy. Additionally, the funds’ investments have protected an estimated 19,500 hectares of land against soil erosion, led to the planting of 39,500 hectares of forest, and reduced the equivalent of 18,500 tons of CO2 emissions. As a result of its success, informal knowledge-sharing with neighboring countries has been scaled up into a formal educational platform, supported by UNDP and the Republic of Korea.

PHOTO: CYRIL NDEGEYA/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

While a net-zero transition may present some financial risks for investors, it also creates an opportunity for blended financial tools to offset those risks, develop new green technologies, gain access to markets, and build resiliency in supply chains. To that end, the private sector has a key role to play beyond mobilizing capital. The world’s largest companies face up to $1 trillion in climate change-related business risks, but the consequences of inaction on climate change extend across their labor and human rights record, supply chain resiliency, operational security, and industrial competitiveness. In the face of climate-relate risks, some promising initiatives have emerged, such as Transform to NetZero, which brings together major companies with the Environmental Defense Fund, a U.S.-based non-profit, to produce Climate Transition Action Plans to facilitate a reduction in their supply chains’ emissions. Another example is Patagonia’s Regenerative Organic Certification (ROC) program, launched in partnership with the Organic Cotton Accelerator, which provides education and training to local farmers in India on soil-regenerative agricultural practices to sustainably increase their outputs while keeping inputs steady. Initiatives such as these exemplify the types of partnerships and investments that need to be scaled up, adapted, and replicated globally to expand skills training and workforce transition, tools, and knowledge sharing around the world to support livelihoods, strengthen environmental stewardship, and advance climate justice.

The interconnected and multivariate threats that climate change poses to the global economy and international security underscore the urgent need for greater cooperation and collective action. Although the compounding effects of accelerating climate change are disproportionately threatening lives and livelihoods in LDCs and SIDS, their mitigation and adaptation capacities remain under-resourced. For decades, developing economies have called for greater financial support from wealthier countries and major polluters. In the face of inadequate financing and inconsistent follow-through by advanced economies, LDCs and SIDS that are most affected by climate change and face an existential threat have renewed calls for change through transformative resource mobilization to address loss and damage, support resilient economies, safeguard infrastructure, and enable inclusive adaptation. For communities that are most climate-vulnerable, these issues are central to the COP 27 agenda and key not only for advancing climate justice but also for, ultimately, ensuring survival.

Acknowledgements

Illustration by Klawe Rzeczy for FP Analytics/Getty Images photos